The Prospects Of Return After 13 Years Of Displacement - Dr. Khalil Gebara

The Prospects Of Return After 13 Years Of Displacement

Dr. Khalil Gebara (Academic and Researcher )

Over the past years, the concept of "migration diplomacy" has developed to become a fundamental challenge for many countries, especially the European Union.

"Migration diplomacy" can be defined as a policy used by states when their position becomes strategic in the global migration system in pursuit of political or economic goals.[i] Countries such as Turkey, Morocco, and Tunisia have benefited from this strategy to achieve financial and economic goals and alleviate the criticism they face regarding restrictions on public freedoms and rights.

The announcement by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, of aid worth one billion euros in support of Lebanon’s stability can be considered a success for the Lebanese government in implementing migration diplomacy, primarily since these funds are not associated with the implementation of economic, financial, and sectoral reforms.

Many political groups criticized the European announcement made during the recent visit of the President of the Commission to Beirut, accompanied by the President of Cyprus.

These political forces described the announcement as a bribe to the Lebanese government in exchange for displaced Syrians remaining in Lebanon. These figures and parties presented proposals for alternatives, such as fully opening the maritime borders and organizing travel across the sea for those wishing to go to Europe.

However, a fundamental question remained absent, and it is time to ask it:

Was Lebanon initially preparing for a safe, organized, and dignified return of displaced Syrians, and did the European bribe disrupt this process? Or are all political forces, with all their differences and diversities, still running since 2011 in a vicious circle based on mixing slogans, concerns, principles, and humanitarian commitments?

In trying to answer the previous questions, let us quickly return to the recent years.

Since 2011, Lebanon, with its multiple sectarian and party formations, has witnessed sharp divisions over the way to deal with the Syrian displacement crisis. At the same time, many initiatives attempted to find common denominators to address how the official state institutions, including central and decentralized authorities, should deal with waves of displacement exceeding one and a half million people.

This difference resulted from Lebanese divisions over their approach to the Syrian crisis since March 2011. The intervention of Lebanese forces in Syria exacerbated the division. This vertical division in the approach to this file was reflected in the relationship with the international community and donor countries. It was demonstrated several times during the participation of official Lebanese delegations in international conferences.

It is no secret that this difference was projected onto the numbers used in official literature over the past years concerning the scale of the crisis and its economic repercussions. The statements were determined by the officials' backgrounds and political orientations, so it became difficult to differentiate between the economic consequences of the Syrian crisis on Lebanon and those of the displacement crisis.

Previous governments attempted to create a state ministry to handle the file and form ministerial and technical committees. However, these attempts failed and did not make a qualitative difference in putting this crisis on the treatment path.

Many topics have sparked a lengthy debate within Lebanon related to how Syrian displacement has been managed since the first batch of displaced Syrians began entering the northern border areas in May 2011.

These topics, a group of no’s, have become fundamental pillars of the "no policy" policy.

The first no was to call displaced Syrians "refugees" because of the entailed human rights repercussions related to protection or settlement, according to official statements and positions of Lebanese officials at home or in international conferences and forums.

The second no was related to gathering the displaced in camps inside Lebanon or on the Lebanese-Syrian borders due to the experience of the Palestinian camps from Ain al-Hilweh to Nahr al-Bared.

The third no was adopting a legal framework regulating the UNHCR and organizing its relationship with Lebanese official administrations. Although the UNHCR started working in Lebanon in 1964, it remains to this day without a headquarters agreement that regulates its work in Lebanon other than the MoU with the Lebanese General Security in 2003 to handle the files of asylum seekers in UNHCR offices, which focused on processing Iraqi refugee files.[ii]

In addition to the sharp Lebanese division over the outlook on the Syrian crisis and the relationship with the regime, these no’s make any attempt to develop a comprehensive scientific and practical approach to managing the Syrian displacement file ended in failure. The inevitable result of what was mentioned above is that the management of this file was transferred to the custody of international and local institutions and organizations. It no longer became the responsibility of the official institutions that failed, over the past years, even to create a national database that include the numbers and locations of displaced Syrians in Lebanon.

In October 2014, the Lebanese government attempted to establish principles to manage the issue centered around the following objectives, which are still applied today:

● Reduce the number of displaced Syrians by banning their entry into Lebanon and encouraging Syrians to return to Syria or other countries.

● Stop the UNHCR from registering displaced persons.

● Establish standards that regulate the entry process of Syrian citizens into Lebanon.

● Strengthen municipal police and direct municipalities to count displaced Syrians.[iii]

Today, 13 years after the first displaced Syrians crossed into Lebanon, the outstanding issues remain the same. The divisions were reflected in conflicting mechanisms by different ministries or municipalities dealing with donors and local and international NGOs. The most prominent example of this may be the disparity in the number of displaced people mentioned by administrations and officials, quoting random numbers to show the burden of the displacement crisis on Lebanon.

In January 2024, a new development took place when the UNHCR provided the General Security with registered refugee data. The data does not include the date of arrival of the displaced to Lebanon or their places of arrival from Syria. However, it can serve as a a base to create the first official database through which the numbers of Syrians in Lebanon are unified and their whereabouts are determined.

According to the UNHCR figures, there are 1.5 million registered Syrian refugees before and after 2015.[iv] There have also been 350,000 Syrian births in the country since 2011, 80% of whom did not complete their birth registration due to administrative obstacles and the high costs of registration in the Syrian embassy in Lebanon.

Nevertheless, the burdens of the Syrian displacement are many and have worsened as Lebanon entered an economic and financial crisis. According to the World Bank report issued in December 2023, the Lebanese economy was able to find in 2023 a temporary bottom following years of sharp contraction a, and Inflation is projected to accelerate to 231.3 percent in 2023. [v].

This economic collapse was accompanied by a disintegration in institutions, an increase in tensions between the Lebanese people and the displaced Syrians, an increase in security incidents and crime rates, and an increase in competition for job opportunities between the Lebanese and the displaced, especially in the informal sectors.

According to media reports, the Lebanese Prime Minister Office estimates the cost of the Syrian displacement at $1.7 billion annually,[vi] equivalent to 9.5% of the GDP in 2023.

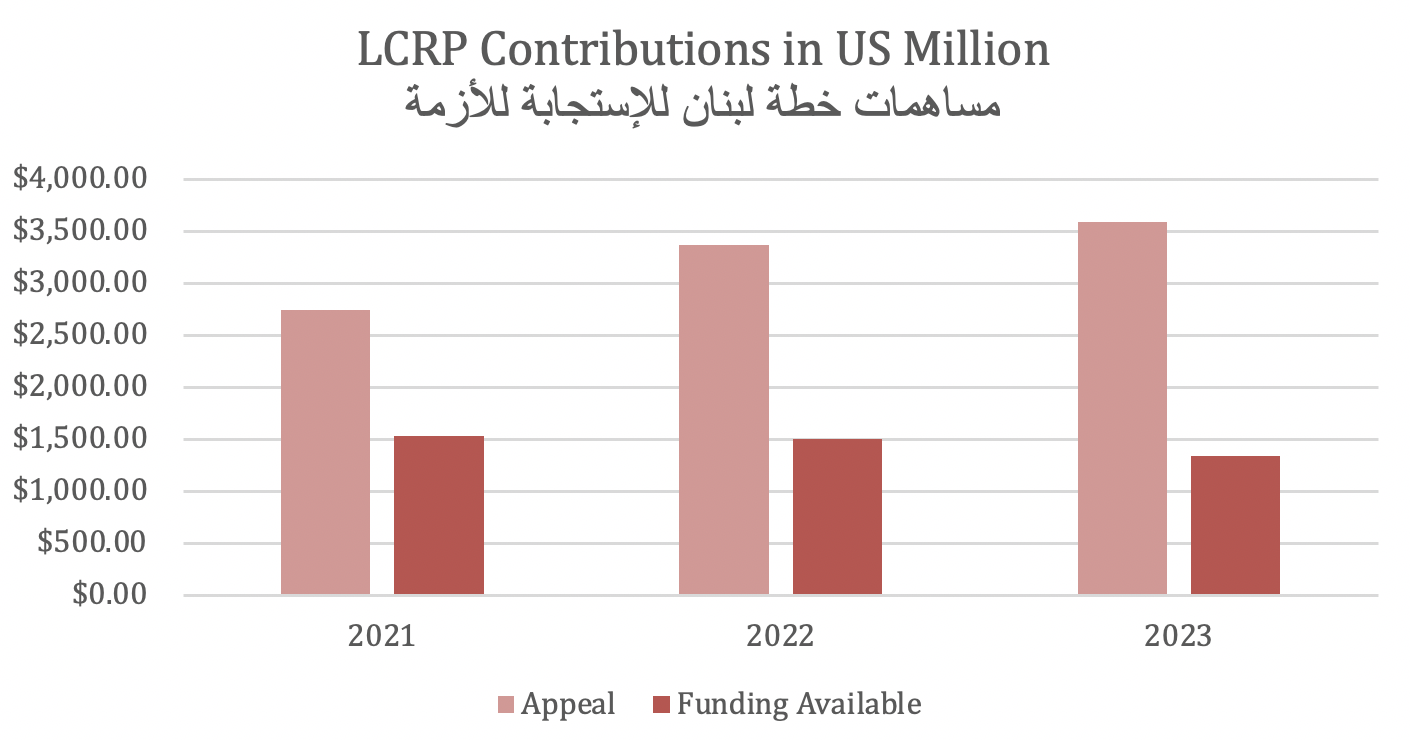

According to data from the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan (LCRP), which is concerned with supporting displaced Syrians and their host municipalities, issued by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, since 2015, Lebanon has received contributions estimated at $9.3 billion within the framework of the LCRP.[vii]

Source: The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Lebanon.

In 2021, the allocated funds were estimated at approximately $1.530 billion, divided between new contributions and those carried over from 2020. These grants constituted 56% of the amounts required to implement all the projects and activities mentioned in the plan.

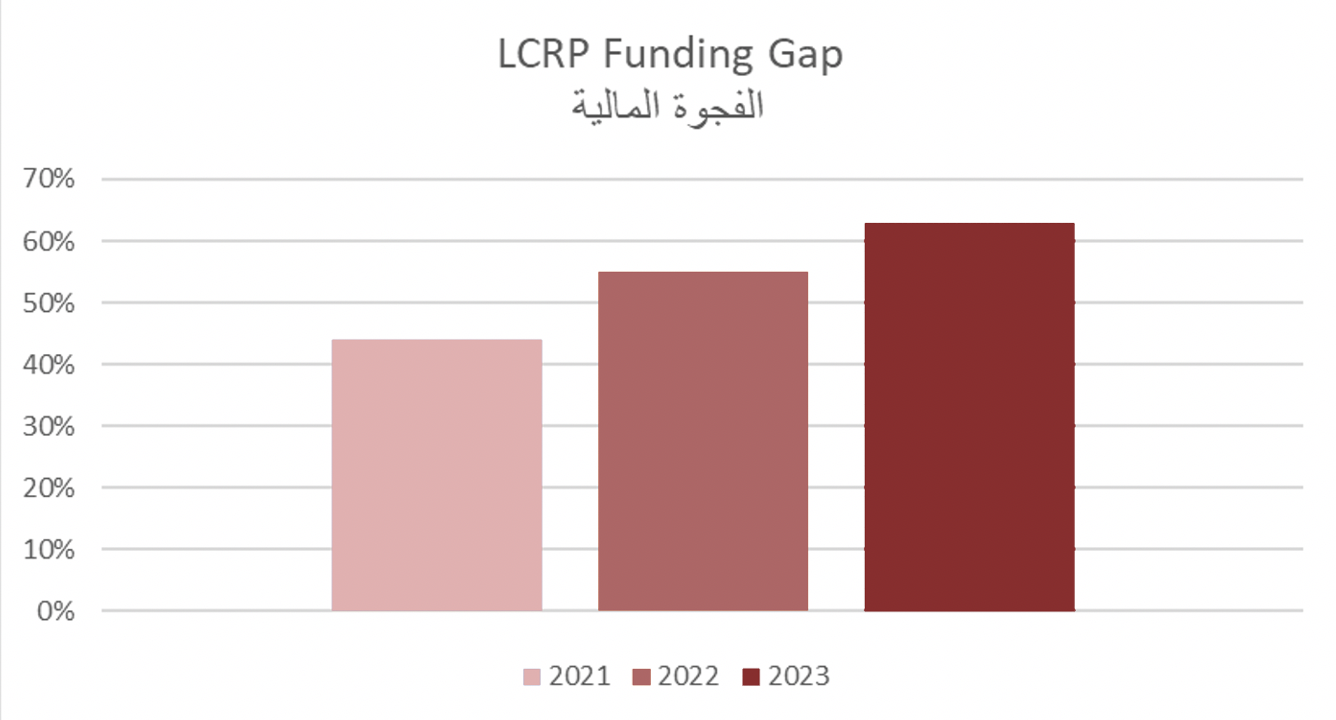

The allocated funds for 2022 amounted to $1.503 billion, representing 45% of the amounts required to implement all the projects and activities mentioned in the plan. Meanwhile, the funds allocated for 2023 amounted to $1.337 billion, representing 37% of the contributions required to implement all projects and activities.

Since 2011, donor countries and organizations have been relied upon to cover the cost of the Syrian displacement in Lebanon. Over the past years, 80% of this cost has been covered. The remaining twenty percent is the direct cost of displacement on infrastructure and public services such as electricity, water, and waste.

However, all forecasts today indicate that the gap between financial resources and contributions from donor countries and the cost of covering the burdens of the Syrian displacement is likely to expand due to foreign countries reducing their contributions due to the wars in Gaza and Ukraine and their economic situation.

Source: the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Lebanon.

However, if the Lebanese authorities handled this new crisis in the same way they did with the economic and financial crisis, by ignoring it and considering that time would solve matters, it is likely to increase popular objection to the presence of the displaced and lead to waves of violence, social tensions, and security incidents.

Therefore, it is no longer a luxury to demand a halt to the political exploitation of this crisis and the belief that it can remain as a crisis without a horizon. It is imperative to focus on practical steps by the government and the relevant ministries that contribute to laying the foundations for the safe, orderly, and dignified return of the displaced Syrians. The practical steps are based on the following:

● Develop a national database for displaced Syrians based on the data provided by the UNHCR and continue to pressure it to complete this data by submitting the registration dates of the displaced, their phone numbers, and the places they came from in Syria.

● Establish a clear policy for Syrian workers, specifying the sectors in which they are permitted to work and the mechanisms for regulating them, through agreements signed between the two sides in this framework.

● Turn to the Arab countries that have restored diplomatic relations with the Syrian regime to help and contribute to supporting the return of displaced Syrians, which will benefit Lebanon and Syria.

● Demand that Western countries and the UN change their current approach in addressing the crisis as if it were without a horizon or time limit and consider a political solution as a prerequisite for communicating with the Syrian regime regarding the return of the displaced and contributing to the rehabilitation of the devastated Syrian areas.

● Control the movement of entry and exit of the displaced Syrians at border crossings and prevent the re-entry of displaced persons registered with the UNHCR into Lebanon.

● Reach an agreement with the Syrian side to organize “Go and See” visits, which are assessment trips organized by and for the benefit of the displaced. These visits aim to assess the security situation, available services, infrastructure, and livelihoods in their areas inside Syria to ensure that an informed decision is made regarding their permanent return.

● Give official visits to Syria by some ministers in the caretaker government a practical and applied dimension away from broad headlines in order to formulate a clear memorandum of understanding that sets the foundations for return, regulates the roles of all parties, and simplifies all procedures and steps such as approving ID papers, birth certificates, and school certificates.

Many developments have occurred in Syria, Lebanon, and neighboring countries since the first waves of displacement inside and outside Syria in March 2011. Although the Russian military intervention in Syria in 2015 was able to change the results of the war, the regime and its allied forces certainly did not succeed in managing the peace phase, reviving the economy, and restoring the infrastructure. The economic crisis, high prices, the diminishing purchasing power of Syrian citizens, and the lack of public services are among the main obstacles that prevent their return to their country. In addition to these factors, there is the absence of political reconciliation, an incentive, and an essential condition for return.

In Lebanon, tensions and security incidents between displaced Syrians and Lebanese citizens have escalated significantly since 2023. As noted in this study, several factors have fueled these tensions, such as the ongoing economic crisis since 2019, competition in the labor market, and demographic concerns. All of these factors are likely to continue over the coming years, which portends an escalation in violence, especially in light of reduced funding for the cost of the Syrian displacement by donor countries.

Therefore, despite the many doubts about the Syrian regime's intentions and desire for the return of the displaced, it has become necessary to work seriously in Lebanon to establish rules and foundations in preparation for that return. This is what this study attempted to present in terms of regarding practical and scientific proposals, away from the prevailing populist discourse.

Dr. Khalil Gebara (Academic and Researcher )

References:

[i] Taub, Amanda “The Dark Incentives that Led to the refugee Tragedy”, The New York Times, June 23, 2023 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/23/world/migrants-smuggling-refugees.html.

[ii] Hala El Helou (2014) Lebanon and Refugees: Between Laws and Reality (Unpublished Master’s Thesis, MA in International Affairs, Beirut, Lebanon p. 43.

[iii] Nassar and Stel, “Lebanon’s Response to the Syrian Refugees Crisis: Institutional Ambiguity as a Governance Strategy”, Political Geography 70 (2019), p. 47.

[iv] LBCI, May 2, 2024 https://www.lbcgroup.tv/news/lebanon/769837/منير-عقيقي-للـlbci-لبنان-تسلم-داتا-النازحين-بعد-جهد-جهيد-وتضمنت-مليونا/ar

[v] World Bank Group Lebanon Economic Monitor Fall 2023 (Washington DC: World Bank Publications, 2023) p. xi.

[vi] عقيل، ملاك أساس ميديا، حبة المورفين الأوروبية توحد الغضب على ميقاتي، ٥ أيار ٢٠٢٤ https://www.asasmedia.com/66920

[vii] https://lebanon.un.org/en/110415-aid-lebanon-tracking-development-aid-received-lebanon.

Recent publications

Related publications