Beyond Promoting the Role of Lebanese Women in Parliament - Jana Dhaybi

Close to the Lebanese parliamentary elections scheduled for May 15, 2022, we begin to hear the seasonal discussion of the modest percentage of women candidates, which did not exceed 15% of the total nominations this year.

Lebanon does not impose legal restrictions on women's participation in political life. However, it has yet to legislate "positive" laws that encourage women's political and representational empowerment, unlike several countries in the Arab region. The situation prompts the following questions. What are the reasons for Lebanon's delay in achieving a balanced representation of women in Parliament? Are the obstacles purely legal or are they rooted in the nature of Lebanon and the composition of its regime?

Facts and Figures

In mid-March 2022, the candidacy period set by the Lebanese Ministry of Interior and Municipalities ended with 1,043 candidates, including 115 women. The percentage of women candidates reached 15%, a 4% increase from the last elections (2018). At the time, 6 out of 84 women candidates won, taking 4.6% of the 128 parliamentary seats.

The history of prejudice against women is apparent. Looking at post-civil war parliaments, surveys by Information International have shown the following facts. In 1992, 3 women entered parliament out of only 6 candidates. In 1996, 3 out of 10 women candidates won, and, in 2000, 3 out of 15 women candidates won also. Although the number of women candidates increased during that period, the number of winners remained the same.

In the 2005 elections, 6 out of 16 women candidates won. However, in 2009, the number was reduced to 4 winners out of 13 women candidates.

Nevertheless, most Lebanese women MPs did not enter parliament in a genuine manner, independent of men. Rather, it was because they were wives, sisters, widows, or daughters of politicians and martyrs. They automatically became responsible before public opinion for protecting the heritage of those men who paved the way for them to Parliament and for defending the gains of their parties, even at the expense of women's votes and rights.

Discriminatory Electoral Law

The Lebanese electoral law seems to be the number one enemy of women. After the civil war (1975-1990), this small country, which includes 19 sects, distributed its parliamentary seats (128 seats) equally between Muslims and Christians. The current electoral law, approved by Parliament in June 2017, is based on the proportional system. It divided Lebanon into 15 districts encompassing the 27 cazas. The small districts led to blatant sectarian division.

One of the flaws of the law is that it does not allow individual candidacy and requires each candidate to be on an electoral list. It allows voters to elect one list in the district in which they are registered and give a preferential vote exclusively to one list member.

Therefore, the law was seen by many to favor the political elite that maintains the patriarchal system, establishes its legitimacy, and preserves the gains of those in power.

Accordingly, the battle of independents and opponents has become more complicated, particularly over women candidates who do not come from political homes and families. They also lack the tools to fight the battle the Lebanese way, including sectarian, regional, and family fanaticism, legal impunity, lavishing political money, and covering the costs of electoral machines.

The Lost Quota

On the other hand, Lebanon has not adopted a women's quota in its electoral law. At the end of 2021, Parliament decided to reject the question due to opposition from most of the political parties within the parliament. The women's quota bill dates back to 2006, when it was put forward by the National Commission for Parliamentary Elections Law. The bill proposed a 30% quota in and their approximate representation in Parliament.

The draft law had been subject to bickering and postponement in the previous years, despite its adoption by a number of parliaments in Arab countries such as Tunisia, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Sudan, Egypt, and Morocco. So what is the reason behind Lebanon's delay?

Formally, most of the major parties in Parliament claim that the quota system might cause a sectarian balance in seats. In addition, they claim it is difficult to calculate in a way that preserves and guarantees the distribution of parliamentary seats according to the sectarian and regional system. However, and in addition to dividing parliamentary seats equally between Muslims and Christians, Lebanon also lags behind in gender-related legal standards that empower women as equal partners with men in the country.

Why focus on the role of parties?

Political parties are directly responsible for the conditions of women. They are the most organized institutional framework in political life and a wide door for them to enter parliament. In an overview of the Lebanese parties, whether traditional or newly established, we notice their indifference to the nomination of women or to putting them at the forefront of their work. Each party has its own position in this regard, whether ideologically, culturally, socially, or politically, or because they do not have enough confidence in the equal participation of women.

Most Lebanese parties give women secondary roles in their offices. They are satisfied with formal presence, without giving them the tools to contribute and influence partisan work in the deep political sense. Their presence is absent from ideological parties.

The strangest paradox is that the same parties whose behavior expresses a deep-rooted belief that “politics is for men” deliberately form committees dealing with “women’s affairs.” Slogans supporting women are raised within the patriarchal and traditional patterns, as the mother, sister, wife, breadwinner and housewife, without initiating real changes in the lived reality, and the absence of clear mechanisms and programs to activate their participation.

Roots of the crisis

In fact, the inevitable link between women's political empowerment and the 15 personal status laws regulating families cannot be overlooked whether in Christian or Muslim sects. This type of pluralism has entrenched the grievances of women to varying degrees from one sect to another, due to the absence of a just and unified personal status law.

The Lebanese constitution grants sects an exceptional authority to manage personal affairs, with issues of minimum age of marriage, divorce, alimony, custody, and inheritance. The "Gender Justice Assessment" issued by the United Nations on Lebanon in December 2019 showed that Lebanese laws do not support gender equality and do not provide adequate protection for women from violence.

Although the Lebanese Constitution of 1926 states in Article 7 that “all Lebanese are equal before the law and enjoy equal civil and political rights," it does not explicitly refer to gender equality and does not prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex or gender.”

The problem, then, is: How will Lebanese women achieve the right to equality in political life, when laws deprive them of equality within the family, the smallest societal unit?

The struggle of Lebanese women

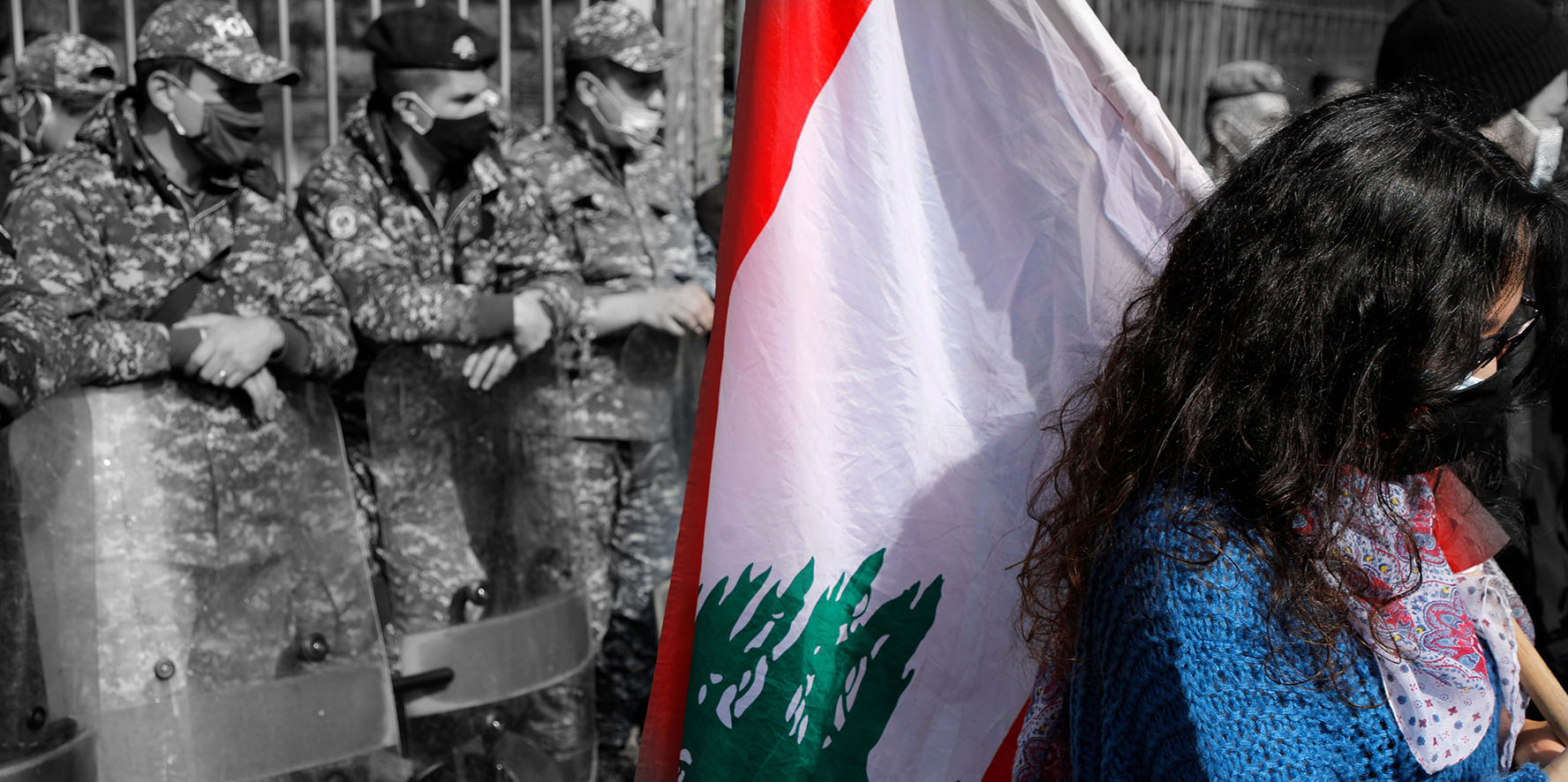

Lebanon's history is overflowing with the political, social, union, and civil struggles of its women. Perhaps what he witnessed since the October 17, 2019 uprising was the best evidence of the strength of Lebanese women and their pivotal role in the squares. However, experience has proven that the strength of presence on the ground, although a major factor, is not enough to achieve women’s rights, especially when they face the wall of discriminatory civil and sectarian laws.

Due to the alignment of political and religious authorities since Lebanon's inception, women have been battling on two fronts. The first involves legislating civil laws in the male-majority parliament. The second concerns personal status laws in religious courts headed by religious judges.

As we approach the elections, women are facing great challenges, which have multiplied by the unprecedented crisis in Lebanon. As the main victims of the sectarian and discriminatory political system, the failure to overthrow it or at least weaken it, means that women will suffer the most from granting the same political class parliamentary legitimacy for four new years.

But, does this lead to despair? Of course not, especially if this election is going to be the foundation of a new phase in which Lebanese men and women will battle for reforming and changing laws to serve the public interest and attain justice and equality.

Jana Dhaybi

Recent publications